Written by Ted Goslin

Written by Ted Goslin

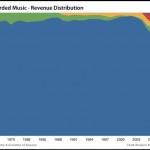

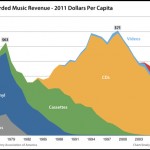

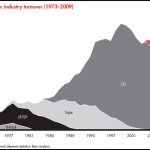

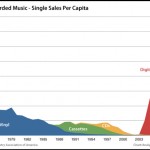

Anyone who follows music knows how much the music industry has changed since the beginning of the century. The biggest change is perhaps in how much money the music industry brings in today. The peak hit around the year 2000 with just under $70 billion in profits for recorded music according to the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). The current amount is under $30 billion, giving it a 64 percent drop from its peak.

As the steelpan climbs to its most popular era in history, gaining new players, composers, arrangers and educators every day, a big question comes up amongst most people in steelpan circles: how can steelpan recording artists make money? To arrive at an answer, one must first look at the history of steelpan recordings. For as long as the instrument has been in existence, there have been recordings of the steelpan. Most of the early recordings originated from its home in Trinidad & Tobago, with one song, “Lion-Oh” by Roaring Lion (1940), gaining recognition by some as being the first known recording with steelpan.

Other recordings branched out across the Caribbean and into other countries like the United States over the years, with the instrument landing on popular recordings of calypsonians and outside recording artists, while also gaining attention as an ensemble instrument with the beginnings of Panorama in the 1960s. Suffice it to say, the more recording artists and producers who heard the instrument, the more who wanted to record it.

Chance Encounters

By the time the 1970s and 1980s rolled around, the instrument was more popular than ever, both with the popular Delos series of Panorama recordings and the instrument being used in mainstream music like “Kokomo” by the Beach Boys and film scores like “Star Wars,” “48 Hours” and the Arnold Schwarzeneggar action film, “Commando”. The latter two, scored by the late James Horner, utilized the services of famed American steelpan artist Andy Narell, with help from his brother Jeff Narell, Robert Greenidge and Tom Miller of Pan Ramajay.

“I first connected with James Horner through Andy. He suggested I play on ‘Commando’ because he was contracting pan players. I had known Andy for several years from master classes he did in the mid-West. I had just moved to L.A. for a while but stayed in touch with him and we got pretty tight,” said Miller. “When he contracted the session he was living in the bay area and I was living in L.A. He needed players who could read music. Most pan players in L.A. at the time were from Trinidad and are really good and I always held them in high regard, but none could read music. I got my first contract from [Narell]. After that, it was just the LA hustle. I got a fair amount of jingle work at the time. Producers wanted me to read charts down and I was out. I never felt like the best pan player in L.A. but felt like I had an edge because I was one of a few that could read.”

Andy Narell got his start in recording at a young age in a similar way to Miller, with his first studio session coming at age 15 in New York. “I don’t remember how the contact came about, but I went with my dad to see two guys who were producing music for commercials, and they couldn’t believe they’d met a pan player who could read music,” said Narell “What I remember best about the session was that on the break Ray Barreto and his buddies played some rumba, which I didn’t know anything about at the time, but I loved it.”

Shortly after moving to San Francisco, Narell took a chance and made a cold call to David Rubinson, a producer of acts that included Herbie Hancock, Santana and the Pointer Sisters. Narell mentioned an audition his band had with him in New York, which didn’t go well. Luckily, Rubinson took the call due to his needing a steelpan player for a recording session who could read music. Narell played his first session for him a few days later. “In the following years he hired me to play one tune with Taj Mahal, Moby Grape, Phoebe Snow, Patti Labelle, Peter Paul and Mary, The Pointer Sisters, etc. I got to work with Fred Catero on those sessions, one of the premier recording engineers of that era. Roy Halee too.”

Narell also made contacts through street performing, having spent a summer traveling and playing his pan on the street for change. “I was back in San Francisco and was playing outside the Cannery when Bernie Krause walked by and heard me play Bach. He was intrigued, gave me his number, and told me to call him,” said Narell. “I didn’t know who Bernie was at the time (Beaver and Krause – synthesizer pioneers) but it turned out to be a big break. I started playing keyboards and arranging for him – commercials mostly, but also films and records. I was a beginner arranging for strings, horns, and vocals, but he let me learn on the job. We would record basic tracks, strings, horns, background vocals, lead vocals, narration, synth overdubs, and mix – a thirty and sixty second version of a commercial in one day’s work. It was recording school for me, and I started getting to know the good musicians in town, like Mel Martin; he and I put together the first jazz band I played in.”

After starting his jazz band, making a couple of albums and playing small festivals in California, Narell caught the attention of James Horner through a percussionist friend, Larry Bunker, who played timpani on film scores in Hollywood. “Working with James I got known pretty fast as the pan player who could read and improvise, so for a while I had a lot of interesting and good paying work with him, Maurice Jarre, Michel Colombier, Elmer Bernstein, Hans Zimmer, and Thomas Newman. James often wanted more than one player, and I did a lot of those sessions with guys like my brother Jeff, Robert Greenidge, Bryan Parris and Tom Miller. I also did quite a few commercials and album dates in L.A. at that time.”

One of the most well-known pannists in the mainstream recording industry is Robert Greenidge, who landed the gig of a lifetime playing full-time with Jimmy Buffet and the Coral Reefers Band as their permanent double second player. Greenidge, known as one of the premier players, composers, and arrangers in Trinidad, has also been a force in the recording industry on film scores and albums with famed artists like Buffet, Taj Mahal and others.

“Robert Greenidge is a great player and was the first guy to start playing a double second soft in the studio as a way to get the sound out front. Check out ‘Just the Two of Us’ and his other work with Ralph McDonald, etc. He recorded one track with this guy but there was no way they were taking a world class pan player out on the road to play one tune. Robert is actually the only pan player I know that has a steady gig touring (Jimmy Buffett), and I wouldn’t call that a career path for young players.”

Today, Greenidge continues arranging for Panorama, while touring with Buffet and has recently recorded the song, “Rum is the Reason” with country artist Toby Keith. However, since it’s just one song, the group uses a synthesizer during live performances.

Learning Your Craft

As Narell and Miller can attest, much of making a name for oneself in the recording industry is who you know. The same can be said for Joseph Peck, also known as “Panhead,” who started much the same way as Miller and Narell, getting a degree in music and playing for anyone who would listen. Making his way out to Los Angeles from Kansas in the early 2000s, ‘Panhead’ would end up making friends with various players and recording artists, while writing and recording his own music for steelpan. Eventually he crossed paths with famed Rock vocalist, the late Scott Weiland, who gained fame as the lead singer for Stone Temple Pilots.

“I came out here with the idea to put steel drums in popular music. That’s like putting a trumpet player with Metallica. I met Scott and one thing really led to another. He was really interested in the steel drum instrument,” said Peck. “I got to record things with different artists like Scott Weiland, Cyndi Lauper and did the soundtrack for the movie ‘Bug,’ a thriller with Harry Connick Jr. and Ashley Judd. It’s been a driving passion of mine to put the instrument int hte context of music that the listener is not used to hearing. That led me to record my first solo album called, ‘Free Flow Steelpan Meditation, Vol. 1.’

As an experienced recording artist, Peck suggests that those looking to record their own albums first learn the ins and outs of their instruments in terms of music theory, performance experience and musicianship. Once those elements are mastered, it comes down to equipment and creating a home recording studio.

“For a pan player to market themselves, the musicianship needs to be taken care of. Then may want to invest in their own recording equipment. The first step as an artist is having a knowledge of the process of recording. Getting a gig in a studio without having an understanding of the technological aspect severely limits what you can do,” said Peck. “What I’ve discovered in the recording studio world is most engineers and producers have never recorded a steel drum instrument. That can go one of several ways. It may turn into a disaster in terms of them not respecting the art form itself or the instrument. For example, I’ve been in some studios where the engineer has no concept of pan and put the mic up above the pan and don’t secure the mic properly and it falls right into the pan. There’s a level of knowledge that a steel drum artist should work on cultivating.”

Being prepared for studio work requires first some personal experience recording oneself at home. Especially given that studio work is few and far between these days and if the player doesn’t have the experience to know what they are doing, the studio may not call them back.

“When I first played pan I had a band called Pandora’s Box. Panyard was selling our album. It was a great experience that we had to record a full steel band in a studio. I was playing pan for maybe three years at the time. I got to experience what that was like working with a producer or engineer. It was key in marketing oneself in having experience with the studio,” Peck said.

As a recording pan player, Peck recommends players acquire their own channel line, which is the equipment used to record their instrument directly, rather than rely on a studio or other musicians to provide them recording equipment. This is done to make sure the equipment fits the instrument. Not all microphones, preamps and compressors work for steelpan. The same goes for the recording software like Pro Tools, Logic and Digital Performer, which are all solid systems for recording.

“A lot of players will talk about how important the microphones are and I spoke to Andy Narell in depth about this. Having a set of Neumann KM54 or KM 64 tube microphones would be the cream of the crop. They don’t make them anymore. Instead, Neumann produced the KM 184 mic, which is great but without the warmth of the tubes. Beyerdynamic MC 930 is a lesser option than the Neumanns. Sort of the poor man’s Neumann is the AKG 451. All three are small diaphram condenser mics.”

There are two families of microphones that are used the most in studio recording: condenser and dynamic microphones. Condenser mics are used for high-frequency instruments like guitar, piano and are generally the best choice for steelpans. Dynamic mics work well with low-frequency instruments like drums and electric guitar cabs. Both types of mics will likely be used for recording a full ensemble like a steel drum orchestra.

While most of this equipment is extremely expensive, it is recommended to have it and can be acquired over time for the average musician with hard work. There are varying price ranges to make it more affordable. A set of Shure SM57 microphones is said by many, including Peck, to be a solid option for both live and studio recording for those with limited budgets.

For those looking to build a home studio, Peck suggests purchasing a Motu 896 MKIII Hybrid preamp and getting it modified by a company called Black Lion Audio. The company, based out of Chicago, modifies recording equipment to replace lower quality factory parts with superior parts to maximize the potential of the unit. “If you’re going into an A-list recording studio, they’ll have between $5,000 and $10,000 preamps. A producer or home recording studio may not be at that level, so you should bring your own. I’ve taken some of my equipment and sent to Black Lion Audio to be modified,” Peck added.

Solving the Riddle

Like any industry, recording requires a healthy balance of technical knowledge, experience, skill and a strong network of relationships to get you where you need to go. With steelpan operating mainly in the competitive and educational sects of the music industry, recording artists must rely on themselves to create and market their own albums, along with the established network of steelpan outlets like Pan Ramajay, Panyard and others that sell albums online. CD Baby and iTunes are also solid sources, despite the service charges involved.

Getting the instrument noticed more in the mainstream will require artists taking more chances with material, according to Chris Wabich, steelpan artist and builder. “Liam teauge is doing fine job of getting it to be taken seriously. Playing Classical music and writing original compositions helps gain notoriety,” Wabich said. “Pieces need to be written just for steel drums. Stop trying to play music that’s already been done. Write only for this instrument so it’s unique and can allow the instrument to be taken seriously. You can do Pharell on marimba. It doesn’t make it sound good.”

To gain more work in recording, Peck believes that players should focus on building relationships and meeting other musicians and producers, considering how he got started.

“In a nut shell, cultivate relationships to get yourself into studios. It’s more about who knows you than who you know and how you relate with other people,” he said. “The same goes for live performances. If I’m doing a gig at a school, the first person I’m going to establish a relationship with is the plant manager or janitor. These relationships are key to having a production go off without a hitch. In the recording studio, its about being really conscientious of who works there, be it the runner, staff assistants, etc. Being genuine, having an open heart and cultivating great relationships is what I found to be really key.”

While the industry has lost money over the years due to the ease of obtaining music through the Internet, steelpan artists still have ways to make a living, but just have to get more creative with how they approach their chosen career paths. Narell believes the answer lies in combining a player’s original sound with other elements.

“Sad to say, but recording studio work is almost non-existent now. I almost never get a call because someone needs to hear a steel pan. The only reason people hire me to play on a recording is if they want to hear me play,” he said. “The recording industry isn’t what it used to be. Records don’t sell, music for films and commercials is mostly produced at home on computers. Live players started being replaced by technology when the first drum machines came along, and computers and samplers weren’t far behind. The writing was on the wall 30 years ago. We’ve gotten to the point where very few people can actually recoup their costs from recording albums.”

Some artists, like Jonathan Scales, have been able to make a living recording albums and touring, much like traditional bands should be able to do in the music industry. But, according to Narell, that lifestyle is hard to achieve and the exception, not the rule.

“I don’t know how much time [Scales] spends hustling to get those gigs (a lot, I would think), but those guys are out on the road playing anywhere they can and crashing on people’s floors, doing whatever it takes, and developing an audience. Not for the faint of heart,” Narell said. “The best answer I can give is to be yourself, get your music out there, and try to develop a reputation for what you do. But don’t count on making a living doing recording sessions. I think the best opportunities for pan players nowadays are in education. I spend a lot of my working life teaching and performing with university and high school steel bands and I love it. Steel bands are a growing phenomenon worldwide and they need teachers and guest artists. We’re all out there trying to figure out how to make music and make a living, and we have to do it without record companies and radio, the old ways of getting known. My business model is basically to try to keep the costs under control, make videos to promote online, and try to get more gigs performing, where I will hopefully also sell a few CDs, which is basically what most of the young musicians I know are doing. So good luck to all of us.”

Steelpan recording artist, Chris Wabich, explains the process of recording double seconds for a studio session.