In the 1970s, there were many names in Trinidad focused on expanding the versatility of the instrument. Those names, including Ray Holman and Len “Boogsie” Sharpe, seemed focused on combining as many genres as possible to elevate the instrument both at home and abroad. But what few were doing was focusing on one genre to allow the instrument to be highlighted and expanded on in that realm. The genre in question is Jazz, and the artist credited by many to be the father of Jazz pan was Othello Molineaux.

Born in Trinidad and Tobago, Molineaux quickly fell in love with the steelpan, learning not only to play but build, tune and arrange for the instrument. After moving to Miami to further his career, Molineaux quickly met legendary Jazz bassist, Jaco Pastorius, and together, the two launched themselves into stardom. Over the years, Molineaux would continue to advance the instrument by recording and performing with artists that included Herbie Hancock, Dizzy Gilespie, Monty Alexander and Art Blakey, to name a few.

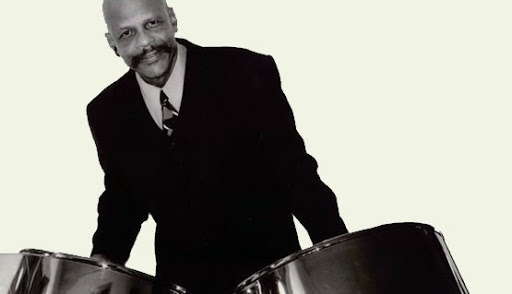

In the first of this two part interview, Molineaux discusses his life, art, instrument, struggles and hopes for the future of pan.

1. Being from a musical family, one that mostly focused on piano and violin, how did you first get introduced to steelpan?

We were a musical family indeed. Father was a violinist, mother was a pianist, sister was a singer, and my two brothers were a pianist and a whistler. I was also a pianist.

When I was about ten we moved next door to a family that had a steel band, and I would look over my wall and watch their rehearsals and their steel drum tuner at work. I noticed that the tuning process involved heating the drum and pounding the drum with a hammer, so I decided to try something on my own.

I got some shoe polish tins and heated eight of them and tuned them into a major scale. I then took them to the wall and presented my “invention” to the guys, played the scale, and found that they were very impressed. I would sometimes go over and play around with their pans when they weren’t there. As a piano player I found it pretty easy to become adept at pan very quickly.

2. How did you get into tuning? Were you also a builder?

Having got the bug after tuning the polish tins, I graduated to the big drums and started to experiment. Nobody actually taught me – it was all trial and error. I might have gotten some tips from a tuner or two along the way as I perfected my craft, but I did not have a teacher.

3. How did you expand your involvement with steel bands?

I might add that, sadly, there was at that time a very disturbing stigma attached to the steel band as having come out of the slums with the associated misbehavior and violence, so kids were not allowed by their parents to get involved.

My parents, as educators and school principals, made us an upper middle class family. So I was not someone who society would have condoned being involved with the steelband people. I was dumbfounded–I could not believe that such a beautiful, artistic expression of our culture, our proud African roots, was denied to so many of us; I was determined to change that.

My involvement in my early teens was actually political. I formed a “stage side” with my close middle class friends. My parents did not object since they knew my friends and that I was their leader.

When I was 16, three of us got a job in one of the most volatile places in Trinidad at the time, “The Gaza Strip,” which was in an area having deadly gangs. The bad guys in them came to hear us play and even poked fun at us. At 17 I joined a band consisting mainly of bad boys: The Invaders. There were only two teenagers in the band besides me. The year was 1957. By 1960 most of these bad guys were gone from the band and replaced by teenagers, I think due to my involvement and influence.

In 1958 I brought my own steelband on the road for Carnival, a band with kids ranging in age from 10 to 18, unheard of at the time. We came out of St. James, making the most profound statement on unifying the classes. My band included kids of the Inspectors of the St. James and Glencoe police, kids of the highest ranking black police official, the acting police commissioner, the son of the principal of the local girls school, the son of a local power proprietor, and the daughter of a Member of Parliament. I enjoyed this experience for two years, having replaced the doubts of the local citizenry with expressions of happy enjoyment.

I then went back to my own jazz band and my piano playing. Then in 1961 I arranged for the Tripoli Steel Band and then took over the band after their positive reaction to my work. We went on the road and included the some of the first women pannists.

4. How did you go about introducing pan into the school system in the Virgin Islands?

Between 1961 and 1967 I arranged for quite a few bands, but the Robin Hood nature in me always made me gravitate to bands needing development. Introducing the pan in schools in the

VI came about in a very intriguing way–the music union’s rule stated that you “could not be provided with a union card if you were not the holder of a green card” (i.e. Permanent Resident), and there were no Trinidadian steel drummers with green cards. So when I had outside gigs, they could not play with me and I had to settle on the St. Thomasian players who were not as good. So I questioned the ruling in the “Daily News,” demanding “Why are the Trinidad players not allowed to play with me all year and then, when Carnival time comes along, the laws are relaxed and they are allowed to play??!!”

That question raised a “Hornet’s Nest” that prompted a response in the daily paper that stated that they did not want any ‘Aliens’ (the name they had for all the people from down the islands) in their carnival and since the steel bands were made up of guys from St. Kits, Antigua and Trinidad, there were no steel bands in the carnival!!

They then realized how important a component the steel band was in the Carnival presentation, and about a month later it was announced that they wanted steel bands in six of the schools. They enquired of me about tuners, and I got the job for my tuner. After the drums were all tuned, there was a call out for arrangers.

Guys came from everywhere to try to get a gig, including a few guys to whom I had to teach simple calypso tunes like “Yellow Bird”–these were guys who were musically illiterate. Because they were from “the birthplace of the steelband,” and ONLY because of this, wanted a job teaching high school! I was shocked out of my mind and profoundly embarrassed.

I then spoke to the powers in charge and advocated that the arranger must be musically literate. This advice was taken in good faith and followed, which led to Mr. Rudy Wells being awarded a scholarship to the College of the Virgin Islands and then to the prestigious Berklee College of Music. The year was 1971.

Obviously there were no steel drum programs in colleges yet. Rudy did it on Vibes. Now, 44 years later, programs in colleges abound!! Rudy, who is a Trinidadian, went back to St. Thomas and is still there. Victor Provost, who was not even born when Rudy went to Berklee, and one of the best players around today, was one of his students. Jonathan Scales, a dear friend and incredible player in his own right, also benefited from the fact that there were so many programs around and the whole steel band community rejoices for the gentle spirit that is Jonathan.

5. After moving to Miami, how did your jazz career begin? What would you say is the most impactful moment in your early jazz career that allowed you to continue on in such a huge way?

My Jazz career started in Trinidad as a piano player. Between 1959 and 1967 I worked in the Jazz clubs with my Jazz band in Trinidad while also doing arrangements and organizing steel bands there.

When I got to Miami there was a radical shift in my priorities, and I decided to focus on the drums, stop playing the piano, and just get to know the steel drum instrument. I wanted to be as spontaneous as possible as a conventional player, thereby introducing Jazz ideas to the steel drum performance.

I quickly realized that there was no finger interplay like we have with the piano. The instrument is played with both hands used equally for striking the desired notes. This element has a very strong physiological significance as the brain no longer has to coordinate two separate functions when playing the instrument such as the coordination of the fret position of one hand with the sounding action with the other hand as with string instruments or the coordination of the valves with the breathing as seen with the majority of the wind instruments.

Although some degree of freedom appears to be lost in the playing of the steel drum because of the absence of finger interplay, the functional equalization of both hands compensates for this apparent loss, and to be as spontaneous as a conventional jazz player you have to make your own rules. I could not love anything more.

In starting to promote the instrument at a time when there was no market for it, I realized that I would be in the unique position of doing what was “best for the pan” as opposed to what was “best for me,” which most of the time did not help me financially.

Case in Point: In the early 1970s, the Miami music scene was very successful, making millions with hit after hit, marketing “The Miami Sound,” i.e. songs like “Rock the Boat” and groups like the “Hues Corporation.” Someone from the Henry Stone Group heard our band and thought that the steel drum would be perfect for the “Miami Sound.” They all thought the sound would enhance and be definitive given the sunshine, ocean and the coconut trees that are Miami. Although it was an opportunity to make some much needed cash. I declined because I did not want the instrument to be exposed initially in America as “part of a manufactured sound.”

It was the early 1970s, the synthesizer was in emergence, and I thought the sound and significance of the instrument might have been lost. I do believe that the instrument would not have been where it is today had I entered into that endeavor. I wanted to first expose the drum to the “Student of the Art” so they could explore its possibilities. So I lost out on some cash there but went on to do percussion forums at the University of Miami, master classes in schools and colleges in the area, and finding work wherever I could. SIGH!! I could have been a millionaire today!

6. When and how did you meet Jaco Pastorius? What was your first impression of him?

After about a year I went into a club where the great Ira Sullivan was playing to audition for a gig there, and I heard some bass playing that just blew me away. I had never heard anything like it. I never imagined in my wildest dreams that a bass could have been played like that! It was ethereal. And the guy also looked like he was from another planet.

Once our set was over, he walked straight up to me and introduced himself. I was humbled and quickly realized that we were a mutual admiration society. Although I kept wondering why this incredible human being, this unbelievably talented person (certainly from another planet) was so impressed with what he heard me do, we walked off to converse privately. As we spoke to each other, we were drawn towards a sort of spiritual quietude, an experience that defined what our involvement would be. We were inseparable from that moment on, and we soon realized that apart from the fact that we loved and respected each other’s playing, there was profoundly more to it. We were kindred spirits, and we were going to spend the rest of our lives making music together. The moment we met was the most impactful moment of my career!

He had heard steel drums before, as this was Miami. He had played on cruise ships, but he had never heard jazz played on them. He was so excited, he had so many ideas for the instrument and its collaboration with conventional instruments, it was mind-boggling. We started and did some beautiful things together, but unfortunately we did not reach our goal.

From the moment we met we were collaborating, as he was planning to do a record with us at some point. But at the same time he was doing his own thing, working with different people, and I had a working band.

In 1976 he auditioned alone for Epic Records and landed a record deal. He came to my home very excited and said “we” got a record deal!” “We”!!!!?? That moment just attested to how much we were one. That signing followed with his first record, which was Grammy-nominated. He had planned to open the record with us doing “Donna Lee” together, but I happened to be in Japan for six weeks at the time.

Othello Molineaux performing with Jaco Pastorius and band on “The Chicken”. Note Molineaux’s solo beginning at the 3:54 mark.

Wow victor nice stuff met Othello back in 90-91.heavy cat.peace